Date: 8/13/06 (Sunday)

Location: Freedman's Ketsugo Bu-Jutsu Kai, Weare NH.

Time: 12:00 / 2:00PM

Cost: $40.00 (Cash Only) no checks

Contact info: Weare NH. Dojo (603)529-3564

Email: peterfreedman@hotmail.com

Web Sight: www.jujutsu.org

Instructor: Peter Freedman Sensei / Guro

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Please bring:

Sneakers

Loosely fitting cloths

Rubber training knife (we have some here for sale $10.00)

Eye protection

Lightly padded gloves

Water & Snack

Note Book

A friend to pair off with

Dues $40.00 cash

Questions - as many as possible

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

No experience required, we will teach you from the beginning & up.

People who already have skill, we will build upon your skill level.

Workshop details:

type of knives used for (self protection) folders - verses fixed blade

grips (holding skills - hand switching skills etc.)

foot work & body angles (attack & evasion skills)

angles of cutting & thrusting (nine basic angles)

hand evasion skills & techniques (offense & defense)

eye exercises (distance control)

breathing technique (fear control / heart beat)

basic first aid (for cuts or wounds)

And much more !

We hope you can come & attend this workshop with a friend to pair off with.

This workshop is open to Men & woman.

No Children, please.

Teenagers 15/16 & up ok, as long as accompanied by a parent.

Law enforcement / Military welcomed - (no discounts at this time)

No group discounts at this time.

Respectfully yours

Freedman Sensei / Guro

Monday, July 31, 2006

Sunday, July 30, 2006

Carlito Bonjoc's Oakland Seminar - August 19th

Carlito Bonjoc will be doing a seminar in Oakland on Saturday, August 19, from noon till 5pm. Carlito is one of the outstanding proponents of Serrada as well as inheritor of his family's system of escrima. I encourage anyone who can make it to attend, as he always shares a wealth of information. I learn a lot from Carlito, and I'm sure you will too!

Lock Position #2 - The Threat Triangle

The “Threat Triangle” is a term I’ve coined to describe the tactical use of the lock position. Again, it is not a static position but an active and responsive tracking method. We want our “guns” facing the main threat, and there are nuances to this orientation as we move relative to an opponent.

The most fundamental is footwork, using the male triangle to face the opponent’s centerline. We lead with either foot, using papeet (replacement step) to orient towards either the left or right sides. If we control the center of the encounter, there are advantages of leverage and shorter lines of movement with the shorter stick.

Our basic consideration is the centerline, which is the most inside line. Our footwork and weapon should maintain directness.

There is also an outside line, which is the widest angle from which we need to guard against the most likely threat presented at that moment.

If we just lock facing forward and the tip of our opponent’s weapon can thrust around our guard, we are vulnerable; think of a rapier or dagger.

Too many people just finish a technique, give a cursory lock, and they’re done, or they just step straight up the center as though that threat had been neutralized. The purpose of the lock is to defend against the next attack. Why assume it will not be with the same weapon, from its previous position? Angel Cabales was a master of the quick thrust, and the lock has to be able to intercept that. For this, angle is critical.

If our opponent is beyond contact distance, the angle between his centerline and outside line is very slight. As we approach, that angle gets wider, and the longer the weapon, the deeper he can reach around us. Visualize his attack as anywhere on an arc, with you in the center of the circle.

At a longer distance, or closer but all weapons forward, our lock can be straight in front. If my opponent’s weapon is off towards my right, that is the side I most likely need to defend, and if he moves the other way, I should be shadowing that direction.

The idea is simple. If I am already in a position that cuts off a surprise attack simply, without resorting to a long or complicated maneuver, my defense will be quicker and more likely to succeed. I don’t want to have to think about a sudden threat when it’s time to react, so if I’m already pre-positioned to intercept that move, I get better use of trained subconscious reflexes.

I can’t always just rotate my body or move my weapon over to cover an angle because I might expose another, more vital one. If the threat you track is a fake, you may have played into your opponent’s strategy.

A good way to solve this is to angle my weapon, using the male triangle principle. For instance, if I am in a right lead, my opponent might be showing a low thrust to my left abdomen. If my weapon is just forward, I’ve left him that gap. If I angle the tip of my weapon back toward the left, my right hand covers the centerline. Both inside and outside angles have proximate coverage.

If my opponent sweeps his weapon to the other side, I would papeet into a left lead. Now the tip of my weapon covers the centerline while my right weapon hand is tracking the opposing weapon. At all times some part of my weapon accounts for every angle his weapon’s got.

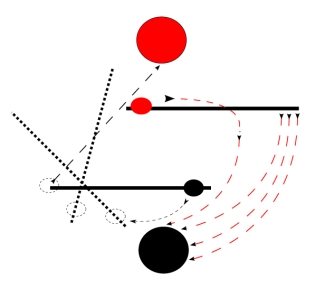

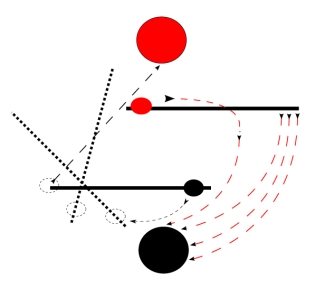

In this diagram, the attacker is in red, the defender is black. The light dotted lines represent movement; the heavier black dotted lines represent the position of Black's stick (and his hand) as he thrusts inward from an outside position.

Notice the entry path available from the end of Red's stick using an arcing strike. There is also a line showing how moving Red's hand over across the body allows even deeper access toward the front of our body. This is particularly important against witiks (snapping blows), especially if sharpened by reverse tapping our own arm to accelerate the effect.

The defender also has a similar angle to counter-attack in this diagram. Black shows a thrust on a direct line from the tip as his hand moves over to compensate. The Threat Triangle is thus the separation by degree of incoming angles we have to monitor, from the weapon hand to the the end of that weapon, as these lines converge on target. In other words, an attack can come from either end of the weapon! We can see this triangle clearly in Black's diagram, using the lines of sight and thrust.

My old Kenpo teacher used to have us imagine having an eye on the toe of our foot. We'd actually place our head on the ground to see what openings that our foot could "see." I do the same thing with my stick, because what is apparent from the tip is different from what I see where my head is located.

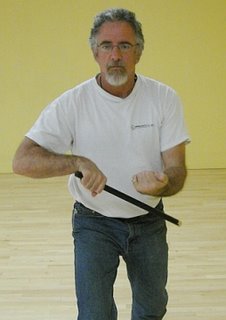

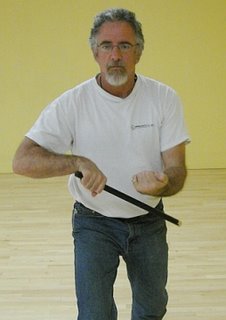

Here I'm facing forward once again, but I'm guarding against an attack from my right, closing off the low line off attack from the tip of an opponent's weapon. Compare the stick position to that in the picture on the previous post. There my opponent's weapon is directly in front and so my angle is more direct.

The most fundamental is footwork, using the male triangle to face the opponent’s centerline. We lead with either foot, using papeet (replacement step) to orient towards either the left or right sides. If we control the center of the encounter, there are advantages of leverage and shorter lines of movement with the shorter stick.

Our basic consideration is the centerline, which is the most inside line. Our footwork and weapon should maintain directness.

There is also an outside line, which is the widest angle from which we need to guard against the most likely threat presented at that moment.

If we just lock facing forward and the tip of our opponent’s weapon can thrust around our guard, we are vulnerable; think of a rapier or dagger.

Too many people just finish a technique, give a cursory lock, and they’re done, or they just step straight up the center as though that threat had been neutralized. The purpose of the lock is to defend against the next attack. Why assume it will not be with the same weapon, from its previous position? Angel Cabales was a master of the quick thrust, and the lock has to be able to intercept that. For this, angle is critical.

If our opponent is beyond contact distance, the angle between his centerline and outside line is very slight. As we approach, that angle gets wider, and the longer the weapon, the deeper he can reach around us. Visualize his attack as anywhere on an arc, with you in the center of the circle.

At a longer distance, or closer but all weapons forward, our lock can be straight in front. If my opponent’s weapon is off towards my right, that is the side I most likely need to defend, and if he moves the other way, I should be shadowing that direction.

The idea is simple. If I am already in a position that cuts off a surprise attack simply, without resorting to a long or complicated maneuver, my defense will be quicker and more likely to succeed. I don’t want to have to think about a sudden threat when it’s time to react, so if I’m already pre-positioned to intercept that move, I get better use of trained subconscious reflexes.

I can’t always just rotate my body or move my weapon over to cover an angle because I might expose another, more vital one. If the threat you track is a fake, you may have played into your opponent’s strategy.

A good way to solve this is to angle my weapon, using the male triangle principle. For instance, if I am in a right lead, my opponent might be showing a low thrust to my left abdomen. If my weapon is just forward, I’ve left him that gap. If I angle the tip of my weapon back toward the left, my right hand covers the centerline. Both inside and outside angles have proximate coverage.

If my opponent sweeps his weapon to the other side, I would papeet into a left lead. Now the tip of my weapon covers the centerline while my right weapon hand is tracking the opposing weapon. At all times some part of my weapon accounts for every angle his weapon’s got.

In this diagram, the attacker is in red, the defender is black. The light dotted lines represent movement; the heavier black dotted lines represent the position of Black's stick (and his hand) as he thrusts inward from an outside position.

Notice the entry path available from the end of Red's stick using an arcing strike. There is also a line showing how moving Red's hand over across the body allows even deeper access toward the front of our body. This is particularly important against witiks (snapping blows), especially if sharpened by reverse tapping our own arm to accelerate the effect.

The defender also has a similar angle to counter-attack in this diagram. Black shows a thrust on a direct line from the tip as his hand moves over to compensate. The Threat Triangle is thus the separation by degree of incoming angles we have to monitor, from the weapon hand to the the end of that weapon, as these lines converge on target. In other words, an attack can come from either end of the weapon! We can see this triangle clearly in Black's diagram, using the lines of sight and thrust.

My old Kenpo teacher used to have us imagine having an eye on the toe of our foot. We'd actually place our head on the ground to see what openings that our foot could "see." I do the same thing with my stick, because what is apparent from the tip is different from what I see where my head is located.

Here I'm facing forward once again, but I'm guarding against an attack from my right, closing off the low line off attack from the tip of an opponent's weapon. Compare the stick position to that in the picture on the previous post. There my opponent's weapon is directly in front and so my angle is more direct.

Saturday, July 29, 2006

Lock Position #1

For those unfamiliar with Serrada, the “lock position” is a signature of the system, an on-guard where our weapon is held in a neutral position more or less horizontally in front of our bodies. It isn’t exclusive to Serrada; grandmaster Navales from Panay teaches it in his system too. However, it is uncommon to most FMA styles and is often misunderstood even by Serrada students.

Here’s how I teach the basic mechanics: I have my students hold their stick out in front around solar plexus level, using both hands pronate (palms downward) to grasp the ends. Simply open the left hand and let that end drop. With a moderate grip, the left end will fall to maybe a 30º angle so the stick is at a diagonal. The left hand stays level with the right hand.

Defenses are typically diagonal - think of kick blocks in empty-hand arts – since low attacks are often horizontal. A vertical triangle like this covers more of your body. The lock position also keeps the weapon in front of you, central to any direction very quickly. If you carry the weapon too vertical, for instance, you have little power to go further in that direction and a longer way down to protect low lines.

Relax your wrist, elbow and shoulder, without going limp. This lets your upper arm cover the ribs better, and you’ll be faster using whipping energy than muscles alone. This lock position might not feel natural at first, but it will. Don’t just push a strike; the strengths of a stick are extension and leverage, which create speed and power. Eventually we want our whole body integrated in each motion, taking advantage of mechanical torque and gravity as power multipliers.

Also consider how much you reach with your hands. A common mistake is to extend outward too far. Remember that your hand is a target, and the farther it reaches, the longer it takes to retrieve. Since the stick is faster than the hand, you’re more likely to get hit if caught reaching. As a general rule I teach our on-guard is from the elbow out. In other words, unless otherwise required, I let my upper arms drop to cover my ribs. I may hold them slightly towards the front of my body rather than more fully relaxed.

Now that we have a basic angle, height and reach, we need movement. The lock position is not static. It’s relational, a way to track and intercept incoming attacks. As Angel taught it, one hand is always moving towards the opponent while the other returns. To get the feel of this, jog in place while holding the stick in the right hand across your body. Notice how the hands naturally fall into a back-and-forth rhythm. This is similar to what you want. However, the movement is not exactly symmetrical, because the weapon should always protect the empty hand and so stays towards the front.

A common error is to reach more with the left hand than with the weapon. This exposes the hand unnecessarily and can possibly interfere with your own weapon being deployed. Keep that left hand behind your primary weapon unless it is being used tactically. After all, our bodies feel pain, our sticks do not, and it’s easier to replace the latter than fix a broken bone. Think of your stick as also being a shield, or perhaps as the bumper on your car, there to take impacts before you do.

I finally got blogger to upload a picture of the lock position facing forward

Here’s how I teach the basic mechanics: I have my students hold their stick out in front around solar plexus level, using both hands pronate (palms downward) to grasp the ends. Simply open the left hand and let that end drop. With a moderate grip, the left end will fall to maybe a 30º angle so the stick is at a diagonal. The left hand stays level with the right hand.

Defenses are typically diagonal - think of kick blocks in empty-hand arts – since low attacks are often horizontal. A vertical triangle like this covers more of your body. The lock position also keeps the weapon in front of you, central to any direction very quickly. If you carry the weapon too vertical, for instance, you have little power to go further in that direction and a longer way down to protect low lines.

Relax your wrist, elbow and shoulder, without going limp. This lets your upper arm cover the ribs better, and you’ll be faster using whipping energy than muscles alone. This lock position might not feel natural at first, but it will. Don’t just push a strike; the strengths of a stick are extension and leverage, which create speed and power. Eventually we want our whole body integrated in each motion, taking advantage of mechanical torque and gravity as power multipliers.

Also consider how much you reach with your hands. A common mistake is to extend outward too far. Remember that your hand is a target, and the farther it reaches, the longer it takes to retrieve. Since the stick is faster than the hand, you’re more likely to get hit if caught reaching. As a general rule I teach our on-guard is from the elbow out. In other words, unless otherwise required, I let my upper arms drop to cover my ribs. I may hold them slightly towards the front of my body rather than more fully relaxed.

Now that we have a basic angle, height and reach, we need movement. The lock position is not static. It’s relational, a way to track and intercept incoming attacks. As Angel taught it, one hand is always moving towards the opponent while the other returns. To get the feel of this, jog in place while holding the stick in the right hand across your body. Notice how the hands naturally fall into a back-and-forth rhythm. This is similar to what you want. However, the movement is not exactly symmetrical, because the weapon should always protect the empty hand and so stays towards the front.

A common error is to reach more with the left hand than with the weapon. This exposes the hand unnecessarily and can possibly interfere with your own weapon being deployed. Keep that left hand behind your primary weapon unless it is being used tactically. After all, our bodies feel pain, our sticks do not, and it’s easier to replace the latter than fix a broken bone. Think of your stick as also being a shield, or perhaps as the bumper on your car, there to take impacts before you do.

I finally got blogger to upload a picture of the lock position facing forward

Saturday, July 15, 2006

Insight Delight

It’s a surprise when something one has done for years suddenly flashes fresh insight. The experience can be both pleasant and disconcerting, the former for obvious reasons of discovery, the latter more a sense of “what took so long?” followed by “What else am I missing here?”

Some things need to percolate and evolve, often waiting for that moment the right question is asked, the key that unlocks the door. We have an “Aha!” moment, but it’s really been there awhile for us to see. It isn’t called “insight” for nothing!

This is also a benefit of teaching, since one is always going over basic information, the raw material feeding our creative unconscious mind. It’s been said (and I’m repeating myself) that UC Berkeley has so many Nobel winners because tenured professors are forced to endure giving those horrid undergraduate courses. This allegedly keeps them grounded in the fundamentals of their disciplines. Same thing here.

So yesterday I had an unexpected insight on “the pass” for angle #3, also known as “the two-step”. Serrada’s angle #3 is thrown as right-handed horizontal forehand slash across the mid-section; the defender sees it coming in left to right. This does what the name implies; it passes the attack through to the other side. In essence, it is an outside parry for a low attack on the left, analogous to the outside block on angle #1. “Inside” refers to being between an attacker’s hands (in front) vs. “outside” which is to the outside of one arm or the other, angled away from the opposite arm.

There has been some controversy within the Serrada community about how this technique is properly done. The majority of people I know do it the way I learned it, which is how Angel Cabales taught the move throughout the 1980’s. The move begins by cocking the left hand and foot, then doing a papeet (replacement step or quick step) with the right leg back. Vincent teaches this as a papeet with the left leg back.

This isn’t insignificant, because it changes the balance, angles and range of the counter-strikes all the way through to the end. Furthermore, there are things in the later version that appear inconsistent with basic Serrada theories, like always facing the attack. Vincent’s method is clearer on that regard. He told me that his way is authentic, and that his father changed the move while training Jimmy Tacosa because Jimmy did it that way.

This never made sense to me, because Angel didn’t do things arbitrarily like that. In fact, I often heard him reply to questions about why certain students would do things differently, by saying “He wants to do it that way and doesn’t listen, so I let him.” In other words, the student might change things, but Angel didn’t follow their lead.

There was a mystery here, a deeper truth to uncover. I’ve always felt I had a piece of this puzzle, because Angel also showed me – once - the footwork pattern Vincent uses, only Angel referred to this as Serrada’s version of a largo mano technique (largo mano is the range where your head is out of your opponent’s reach but his attacking hand is within your reach). Like Vincent, Angel moved back slightly on the first move, then surged in on the counterstrike. (It’s a bit like Sonny Umpad’s “pendulum” this way.)

Since I had seen both versions from Angel, I didn’t think of them as incompatible but rather as complementary. The way I was taught kept things a hair closer, relying more on the check hand to suppress the incoming attack, thereby altering its range. By keeping these as separate and discrete, I didn’t get confused. I spent some time trying Vincent’s version as the “only” way, but it just messed my timing up with either pattern. Once I realized it matched Angel’s “largo” I could keep it safely categorized as an alternative move.

This, however, was an old perspective from 15 years ago. I still had not fully deciphered the reason Angel allegedly changed the footwork so radically. In particular his later method seemed to leave the last strike off-balance and at an awkward angle. This strike is a right downward chop with the right leg forward. While our basic #1 strike steps in like this, here we are stepping back with the left leg, so we do not get the benefit of dropping our weight forward fully into the strike. This actually tends to pull energy away from the blow, which seems odd. I often tried to explain discrepancies as the move setting up for the reverse backhand strike (angle #4) to follow, but that also presented some technical inconsistencies which then had to be explained away.

Then last night as I was teaching this technique to someone new, I heard myself say something I’d never heard or thought before. This was regarding that finishing strike. I’d been thinking for some time that the power comes from torquing the upper body counterclockwise, which was somehow at odds with a vertical right forehand finishing blow. What I heard myself say was “you can chop diagonally to your opponent’s inside, towards the centerline, to take the upper arm.”

This tied together several other pieces of information. I’ve often told the story, related to me by a Modern Arnis teacher who had worked as a doctor in the Philippines, that after knife or sword fights, corpses frequently had cuts to the upper sword arm, but survivors almost never had such a wound. The implication was clear that such a cut incapacitated the loser’s ability to further defend, a good example of “killing the fang.”

What triggered this association was recognizing that if an attacker throws a powerful #3 strike and misses, it will likely carry his arm all the way across his body, removing the forearm as a target, at least until he comes back with the reverse #4 strike. With the forearm out of range, the logical target changes, and the closest and most effective is the upper arm.

This is consistent with defender’s direction of power in that hard torso twist to the left. Using a short chop, followed by a quick abanico to the “lock” position (weapon held across the body in an on-guard position) put one’s focus right on the opponent’s centerline. Previously I’d been targeting back to the forearm, which meant either striking towards my own outside line off the hip (as opposed to keeping power in towards my own center, which is more fundamental to our theories) or stepping wider across my opponent to orient power but exposing my low line to greater extent.

I’m sure others have had this insight too, but I’ve never heard it. There has always been vagueness as to why this technique looked different from so many others. By analyzing the power structure and alignment of both attacker and defender, an odd technique suddenly feels technically sound.

Some things need to percolate and evolve, often waiting for that moment the right question is asked, the key that unlocks the door. We have an “Aha!” moment, but it’s really been there awhile for us to see. It isn’t called “insight” for nothing!

This is also a benefit of teaching, since one is always going over basic information, the raw material feeding our creative unconscious mind. It’s been said (and I’m repeating myself) that UC Berkeley has so many Nobel winners because tenured professors are forced to endure giving those horrid undergraduate courses. This allegedly keeps them grounded in the fundamentals of their disciplines. Same thing here.

So yesterday I had an unexpected insight on “the pass” for angle #3, also known as “the two-step”. Serrada’s angle #3 is thrown as right-handed horizontal forehand slash across the mid-section; the defender sees it coming in left to right. This does what the name implies; it passes the attack through to the other side. In essence, it is an outside parry for a low attack on the left, analogous to the outside block on angle #1. “Inside” refers to being between an attacker’s hands (in front) vs. “outside” which is to the outside of one arm or the other, angled away from the opposite arm.

There has been some controversy within the Serrada community about how this technique is properly done. The majority of people I know do it the way I learned it, which is how Angel Cabales taught the move throughout the 1980’s. The move begins by cocking the left hand and foot, then doing a papeet (replacement step or quick step) with the right leg back. Vincent teaches this as a papeet with the left leg back.

This isn’t insignificant, because it changes the balance, angles and range of the counter-strikes all the way through to the end. Furthermore, there are things in the later version that appear inconsistent with basic Serrada theories, like always facing the attack. Vincent’s method is clearer on that regard. He told me that his way is authentic, and that his father changed the move while training Jimmy Tacosa because Jimmy did it that way.

This never made sense to me, because Angel didn’t do things arbitrarily like that. In fact, I often heard him reply to questions about why certain students would do things differently, by saying “He wants to do it that way and doesn’t listen, so I let him.” In other words, the student might change things, but Angel didn’t follow their lead.

There was a mystery here, a deeper truth to uncover. I’ve always felt I had a piece of this puzzle, because Angel also showed me – once - the footwork pattern Vincent uses, only Angel referred to this as Serrada’s version of a largo mano technique (largo mano is the range where your head is out of your opponent’s reach but his attacking hand is within your reach). Like Vincent, Angel moved back slightly on the first move, then surged in on the counterstrike. (It’s a bit like Sonny Umpad’s “pendulum” this way.)

Since I had seen both versions from Angel, I didn’t think of them as incompatible but rather as complementary. The way I was taught kept things a hair closer, relying more on the check hand to suppress the incoming attack, thereby altering its range. By keeping these as separate and discrete, I didn’t get confused. I spent some time trying Vincent’s version as the “only” way, but it just messed my timing up with either pattern. Once I realized it matched Angel’s “largo” I could keep it safely categorized as an alternative move.

This, however, was an old perspective from 15 years ago. I still had not fully deciphered the reason Angel allegedly changed the footwork so radically. In particular his later method seemed to leave the last strike off-balance and at an awkward angle. This strike is a right downward chop with the right leg forward. While our basic #1 strike steps in like this, here we are stepping back with the left leg, so we do not get the benefit of dropping our weight forward fully into the strike. This actually tends to pull energy away from the blow, which seems odd. I often tried to explain discrepancies as the move setting up for the reverse backhand strike (angle #4) to follow, but that also presented some technical inconsistencies which then had to be explained away.

Then last night as I was teaching this technique to someone new, I heard myself say something I’d never heard or thought before. This was regarding that finishing strike. I’d been thinking for some time that the power comes from torquing the upper body counterclockwise, which was somehow at odds with a vertical right forehand finishing blow. What I heard myself say was “you can chop diagonally to your opponent’s inside, towards the centerline, to take the upper arm.”

This tied together several other pieces of information. I’ve often told the story, related to me by a Modern Arnis teacher who had worked as a doctor in the Philippines, that after knife or sword fights, corpses frequently had cuts to the upper sword arm, but survivors almost never had such a wound. The implication was clear that such a cut incapacitated the loser’s ability to further defend, a good example of “killing the fang.”

What triggered this association was recognizing that if an attacker throws a powerful #3 strike and misses, it will likely carry his arm all the way across his body, removing the forearm as a target, at least until he comes back with the reverse #4 strike. With the forearm out of range, the logical target changes, and the closest and most effective is the upper arm.

This is consistent with defender’s direction of power in that hard torso twist to the left. Using a short chop, followed by a quick abanico to the “lock” position (weapon held across the body in an on-guard position) put one’s focus right on the opponent’s centerline. Previously I’d been targeting back to the forearm, which meant either striking towards my own outside line off the hip (as opposed to keeping power in towards my own center, which is more fundamental to our theories) or stepping wider across my opponent to orient power but exposing my low line to greater extent.

I’m sure others have had this insight too, but I’ve never heard it. There has always been vagueness as to why this technique looked different from so many others. By analyzing the power structure and alignment of both attacker and defender, an odd technique suddenly feels technically sound.

Friday, July 07, 2006

Kelly Worden's Blog

I'd like to welcome Kelly Worden to the world of blogging. His first piece is an article he wrote about growing up in his hometown. Kelly brings a critical honesty to martial arts writing that is both refreshing and bold. You can use this link to get there, or the one I've posted permanently on my sidebar. Congratulations, Kelly!

Sunday, July 02, 2006

FMA's Ship Finally Pulling In?!!

I’ve been actively involved in Filipino martial arts now for over 25 years, and for much of that time I’ve heard that it is about to become “the next big thing” in martial arts.

Judo, Karate, Taekwondo, Kung-Fu, Kenpo, Ninjutsu, JKD, Aikido, Brazilian Jujitsu; the list seems endless for all the arts that have had their moment in the media’s spotlight as the featured flavor. For the most part, the FMA have remained the worst kept secret in martial arts, an insider’s connection that was often hidden in plain view by those who incorporated elements of the training into other styles.

Since the late 1980’s there has been significant growth within the FMA community as there have been more teachers to bring the art forward, promoting various legacies in their own right. Tournaments have evolved to provide opportunities for newcomers to test their courage and skills and to promote visibility to the general public. There have been various full-contact and point rules for both live and padded sticks. Some tournaments have been all-FMA, others have been divisions within other martial art tournaments, but few if any have had access to mass exposure through public media.

THAT IS ABOUT TO CHANGE!

For the past half-dozen years Disney World has promoted the Disney Martial Arts Festival, a monumental event that has grown to include over 1000 athletes in 16 different disciplines ranging from traditional to modern expressions of punching, kicking and grappling arts from around the world. What have been conspicuously absent until now are the Filipino martial arts.

Every competition within the Festival is affiliated with a national organization that creates the formats and rules for their particular art, and which bring competitors together for this event. Disney becomes the sponsor, providing everything necessary to run the tournament, from mats, tables and chairs all the way to medals.

But wait! There’s more! (as they say on infomercials).

DISNEY'S TOURNAMENTS ARE CARRIED ON ESPN2!

That’s right folks. We’re talking martial arts with major corporate sponsorship and national television exposure! This is a world-class event, as close to “Wide World of Sports” or the Olympics as most martial arts will ever get. (Then again, some participating organizations are IOC affiliates …)

Anyway, here is your chance to shine and let your friends and family see you on TV, and for those who are ambitious, you could even try combining different competitions, such as FMA and BJJ, Kajukenbo, TKD, Karate or even Tai Chi or Savate!

Oh, and if you thought one tournament was good, there are two! Disney holds events on each coast; there will be an FMA demonstration at the one this fall in Orlando, then competition will commence in Anaheim in February.

To meet Disney’s protocols and promote FMA participation, a group has been created, the “U.S. Filipino Martial Arts Federation” (USFMAF), whose role is to promote a high quality FMA tournament at this and other sanctioned events.

Over the past couple of weeks a group of volunteers from across the country have met via meetings and conference calls, forming a board of governors that has selected an executive board to take on responsibility for making this tournament a success.

Members of the executive board are:

Elrick Jundis, Executive Director; FMA teacher, promoter and organizer, a strong consensus builder;

Darren Tibon, President; a highly motivated and effective teacher, tournament coach and organizer;

Alex France, Vice President; Secretary General of Ernesto Presas’ IPMAF, FMA teacher, another strong consensus builder;

Darlene Tibon, Secretary General; a key member of Darren’s organization;

Anthony Wade, Treasurer.

I’ve known most of these people for years; they are hard-working, with a love and dedication to the art that is second to none. While this group is all from northern California, that was decided by consensus on a national conference call to facilitate launching an organization on a tight deadline. Moreover, this is a group with depth of experience in promoting tournaments, seminars and other public events. I have no qualms about the quality of this board; it is a first-rate list, and one I am sure will make this event an outstanding showcase competition for Filipino martial arts.

In addition there is one other special mention. Eugene Tibon is Technical Advisor to the USFMAF, and really its godfather. Gene has a list of credentials that would take all day to type, but to be brief, he is our contact to Disney, someone with the credentials to present a new federation to their board of directors and a guide through the ins-and-outs of joining forces with an organization of this magnitude.

More in depth, besides running one of the more successful martial arts chain of schools I know, also Gene holds positions as: President, USANKF of Northern California, Inc.; Regional Sports Organization for Karate; Executive Vice President, USA National Karate-do Federation; Member of the USA Olympic Committee; President, Goju Ryu Uchiage Kai, Western United States; Executive Board Member, City of Stockton Sports Commission. In fact, the list seems to update constantly, as today he said he now has additional roles with Disney’s organization. In other words, he’s been there, done that, knows how national organizations work, and is willing to share his expertise to make the FMA an integral part of this Festival. Already his input has given invaluable insight into what needs to be done to get up and running on short notice.

Now for the best part – everyone is invited!

The USFMAF needs people to work on committees for a variety of things, including: non-profit incorporation and legal issues; a technical committee for rules and regulations; judging and refereeing committee to establish training and standards; equipment (oh yeah – there’s a major martial arts manufacturer that is interested in making whatever gear we need!); medical supervision; organizing committee; etc.

If you think you, your school, your teacher, or anybody else you know in FMA, ought to know more about this tournament, here is a chance to have some input on the ground floor of what could become a major ongoing event. The goal is to be INCLUSIVE, not based on or biased towards one style or organization. Input is both welcome and vital!

Once all these things are done, we get to enjoy a world-class tournament on a national stage! I can say from personal experience, as a participant in world championship tournaments in the Philippines and here in the U.S., that an event like this will long be remembered and be a highlight for a lifetime for those who participate.

This tournament currently proposes a number of formats for competitors. Divisions include both forms and self-defense techniques. Sparring will be both padded and live stick (point fighting); padded single stick (continuous fighting); and live double stick (continuous fighting). There are ideas to expand other areas in the future, but right now the need is to prepare for that first competition.

You can join this group online through Google or go there to contact people. You can also mail me if you need help reaching someone on the executive board.

Judo, Karate, Taekwondo, Kung-Fu, Kenpo, Ninjutsu, JKD, Aikido, Brazilian Jujitsu; the list seems endless for all the arts that have had their moment in the media’s spotlight as the featured flavor. For the most part, the FMA have remained the worst kept secret in martial arts, an insider’s connection that was often hidden in plain view by those who incorporated elements of the training into other styles.

Since the late 1980’s there has been significant growth within the FMA community as there have been more teachers to bring the art forward, promoting various legacies in their own right. Tournaments have evolved to provide opportunities for newcomers to test their courage and skills and to promote visibility to the general public. There have been various full-contact and point rules for both live and padded sticks. Some tournaments have been all-FMA, others have been divisions within other martial art tournaments, but few if any have had access to mass exposure through public media.

THAT IS ABOUT TO CHANGE!

For the past half-dozen years Disney World has promoted the Disney Martial Arts Festival, a monumental event that has grown to include over 1000 athletes in 16 different disciplines ranging from traditional to modern expressions of punching, kicking and grappling arts from around the world. What have been conspicuously absent until now are the Filipino martial arts.

Every competition within the Festival is affiliated with a national organization that creates the formats and rules for their particular art, and which bring competitors together for this event. Disney becomes the sponsor, providing everything necessary to run the tournament, from mats, tables and chairs all the way to medals.

But wait! There’s more! (as they say on infomercials).

DISNEY'S TOURNAMENTS ARE CARRIED ON ESPN2!

That’s right folks. We’re talking martial arts with major corporate sponsorship and national television exposure! This is a world-class event, as close to “Wide World of Sports” or the Olympics as most martial arts will ever get. (Then again, some participating organizations are IOC affiliates …)

Anyway, here is your chance to shine and let your friends and family see you on TV, and for those who are ambitious, you could even try combining different competitions, such as FMA and BJJ, Kajukenbo, TKD, Karate or even Tai Chi or Savate!

Oh, and if you thought one tournament was good, there are two! Disney holds events on each coast; there will be an FMA demonstration at the one this fall in Orlando, then competition will commence in Anaheim in February.

To meet Disney’s protocols and promote FMA participation, a group has been created, the “U.S. Filipino Martial Arts Federation” (USFMAF), whose role is to promote a high quality FMA tournament at this and other sanctioned events.

Over the past couple of weeks a group of volunteers from across the country have met via meetings and conference calls, forming a board of governors that has selected an executive board to take on responsibility for making this tournament a success.

Members of the executive board are:

Elrick Jundis, Executive Director; FMA teacher, promoter and organizer, a strong consensus builder;

Darren Tibon, President; a highly motivated and effective teacher, tournament coach and organizer;

Alex France, Vice President; Secretary General of Ernesto Presas’ IPMAF, FMA teacher, another strong consensus builder;

Darlene Tibon, Secretary General; a key member of Darren’s organization;

Anthony Wade, Treasurer.

I’ve known most of these people for years; they are hard-working, with a love and dedication to the art that is second to none. While this group is all from northern California, that was decided by consensus on a national conference call to facilitate launching an organization on a tight deadline. Moreover, this is a group with depth of experience in promoting tournaments, seminars and other public events. I have no qualms about the quality of this board; it is a first-rate list, and one I am sure will make this event an outstanding showcase competition for Filipino martial arts.

In addition there is one other special mention. Eugene Tibon is Technical Advisor to the USFMAF, and really its godfather. Gene has a list of credentials that would take all day to type, but to be brief, he is our contact to Disney, someone with the credentials to present a new federation to their board of directors and a guide through the ins-and-outs of joining forces with an organization of this magnitude.

More in depth, besides running one of the more successful martial arts chain of schools I know, also Gene holds positions as: President, USANKF of Northern California, Inc.; Regional Sports Organization for Karate; Executive Vice President, USA National Karate-do Federation; Member of the USA Olympic Committee; President, Goju Ryu Uchiage Kai, Western United States; Executive Board Member, City of Stockton Sports Commission. In fact, the list seems to update constantly, as today he said he now has additional roles with Disney’s organization. In other words, he’s been there, done that, knows how national organizations work, and is willing to share his expertise to make the FMA an integral part of this Festival. Already his input has given invaluable insight into what needs to be done to get up and running on short notice.

Now for the best part – everyone is invited!

The USFMAF needs people to work on committees for a variety of things, including: non-profit incorporation and legal issues; a technical committee for rules and regulations; judging and refereeing committee to establish training and standards; equipment (oh yeah – there’s a major martial arts manufacturer that is interested in making whatever gear we need!); medical supervision; organizing committee; etc.

If you think you, your school, your teacher, or anybody else you know in FMA, ought to know more about this tournament, here is a chance to have some input on the ground floor of what could become a major ongoing event. The goal is to be INCLUSIVE, not based on or biased towards one style or organization. Input is both welcome and vital!

Once all these things are done, we get to enjoy a world-class tournament on a national stage! I can say from personal experience, as a participant in world championship tournaments in the Philippines and here in the U.S., that an event like this will long be remembered and be a highlight for a lifetime for those who participate.

This tournament currently proposes a number of formats for competitors. Divisions include both forms and self-defense techniques. Sparring will be both padded and live stick (point fighting); padded single stick (continuous fighting); and live double stick (continuous fighting). There are ideas to expand other areas in the future, but right now the need is to prepare for that first competition.

You can join this group online through Google or go there to contact people. You can also mail me if you need help reaching someone on the executive board.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)